Unpacking the State Budget (Part 2) - Health

Forsyth Medical Center in Winston-Salem, NC - Source: Wikipedia Commons.

Introduction

In many ways, we expect state governments to play some role in our health. States ensure that no one is denied access to emergency care, fund essential public health services and infrastructure, and cover roughly 1/5th of Americans through Medicaid. All of this requires money. Since its passage, no issue in North Carolina’s H.B. 259, the state’s biennial budget for 2023-2025, has received the level of bipartisan support as health spending. In large part, this has been fueled by Medicaid expansion. After fighting it for over a decade, state Republicans have centered behind the proposal, deciding that it is “good state fiscal policy.” Democrats, who have backed Medicaid expansion from the beginning, see it as the silver lining in a bill otherwise packed with poison pills.

While Medicaid expansion represents a massive step forward for NC, it is far from the only health topic covered in H.B. 259 and its addendum’s 1411 total pages. This article, the second in a series on H.B. 259 and its broad-ranging effects, will consider health policy and spending in the bill. From Medicaid expansion to strengthening rural health, we will review the most important issues that North Carolinians expect their state to address and how far H.B. 259 goes to address them.

State Spending on Health

In the US, health does not come cheaply. This is reflected in the state budget. For FY 2023, H.B. 259 appropriates $7.3 billion for health, or roughly a quarter of total state appropriations for the year. However, because Medicaid is largely covered by the federal government (67% in 2020), and because the federal government offers additional block grants to states, this figure significantly understates the $29 billion spent in 2023 in combined expenditures on health and human services in NC—the largest of any category. Whether looking at total spending or just state spending, Medicaid costs account for around 70% of appropriations to the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS).

How does H.B. 259’s health spending measure up to previous budgets? It is much bigger. 2023’s health budget is 21% bigger than that of the 2022 budget after adjusting for medical care inflation (author’s calculations). In the five years before that, the state health budget rose at about the same rate as medical care inflation (author’s calculations). This jump is directly tied to Medicaid expansion. On top of the 90% of Medicaid costs that the federal government pays for the Medicaid Expansion Population, the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) offered states that had not yet expanded an additional 5% federal coverage for two years. In NC, this additional federal funding is worth roughly $1.6 billion. In March, the state legislature passed a bill funneling these extra savings into a reserve fund called the ARPA Temporary Savings Fund within DHHS. The ARPA Fund covers a host of discretionary items in H.B. 259, from workforce training programs and new hospitals to video-game-based STEM education materials for students. Spending from the one-time ARPA Fund and additional entitlement spending caused by expanded Medicaid coverage constitutes the jump in spending from 2022 to 2023. Notably, areas of the budget not impacted by Medicaid expansion or ARPA funds, such as public health, did not receive an annual increase in appropriations.

In short, health spending jumped mostly because of a one-time influx of federal funds given as a reward for expanding Medicaid. This funding shored up some areas of the budget but not others. We should be careful not to extrapolate too much from this jump in spending. The temporary ARPA fund will certainly alleviate areas of crisis and save lives, but it will not fix long-term budget shortfalls caused by NC’s tax cuts. We should not expect jumps in health spending to continue indefinitely.

Key Health Items in H.B. 259

There are hundreds of pages of H.B. 259 dedicated to health spending. The following represent categories of key developments, either because of new developments or a conspicuous lack thereof. These can generally be lumped into the following categories:

Medicaid Expansion

Mental Health

Rural Health

Public Health

Special Issues

Medicaid Expansion

First of all, what is Medicaid expansion? The key piece is expanding Medicaid access to all adults 18-64 living at or below 133% of the federal poverty level. Previously, childless adults and parents making above 36% of the federal poverty level (a brutal $11,800 per year for a family of four) had been excluded. The bill, H.B. 76, which enacted expansion also increases access to mental health and substance use treatment for Medicaid recipients.

Kody Kinsley, NC’s Secretary of DHHS, told news agencies that Medicaid was the “most significant investment in the health of North Carolina in decades.” Governor Cooper cited Medicaid expansion as the sole reason he would not veto the bill, even though he thought other parts of it were flatly unconstitutional. Indeed, Medicaid expansion is the most important health-related provision in the bill, and likely the most important of any provision. The reason is that Medicaid will expand healthcare coverage to roughly 600,000 North Carolinians, slashing uninsurance rates and improving health outcomes. But expansion is also a financial no-brainer, bringing billions of dollars a year of federal funding into the state—increasing revenue in flagging rural hospitals, reducing consumer credit and medical debt, and increasing employment. Besides a huge economic boost to states, research on Medicaid expansion has found benefits ranging from reductions in statewide mortality to better mental health care.

Mental Health

North Carolina’s mental health system has been blinking red for years. The state followed a familiar pattern that played out across the country: state psychiatric hospitals closed and the resources were not invested elsewhere in the mental health system. As a result, emergency rooms have become the provider of last resort for people with mental health crises, even though this is an unsuitable place for them to board because it is loud, chaotic, and typically understaffed with mental health professionals. From here, the average waiting time for an inpatient psychiatric bed is four days, with many cases extending longer. Furthermore, the mental health workforce in NC has been stretched thin, largely due to low reimbursement rates. In 2022, there were 29 counties without any psychiatrists, and 69 counties without a child and adolescent psychiatrist out of NC’s 100 counties. In rural parts of the state, the wait for therapy and psychiatric medication management appointments may reach 10 weeks.

H.B. 259 funds a host of responses to these issues that largely follow the national playbook for addressing the mental health crisis. Most of the solutions address fundamental issues of money, space, and staff—such as the following items and appropriations (listed in 2-year terms) found in H.B. 259’s addendum:

A new children’s psychiatric hospital will be built as part of a new children’s hospital somewhere in the triangle over the next 8-10 years (H-8).

$130 million to increase Medicaid reimbursement rates for healthcare providers of mental health, substance use, and developmental disabilities (C-60).

$18 million for a workforce training center for behavioral health providers (C-99).

$40 million to stabilize a staffing crisis in the 13 state-operated behavioral healthcare facilities (C-73).

$4 million to support the NC-PAL line for physicians in any county to consult an on-call psychiatrist. This effort aims to expand access to psychiatric care in areas where there are no or few psychiatrists (C-60).

$80 million to create new mobile crisis teams, as well as about $30M over 2 years to expand psychiatric bed capacity in existing state hospitals (C102).

$16 million in forgivable loans for early career primary care physicians and psychiatrists practicing in tier 1 or 2 NC counties (C-70).

$20 million in grants for physicians to begin offering telehealth services. Does not apply exclusively to behavioral health providers (C-71).

$80 million in family support services for children with behavioral health or other special needs (C 71).

$15 million in additional Medicaid services for children in foster care (C-61). They had previously been underserved by the system.

$20 million for a centralized registry of statewide inpatient behavioral health beds - BH SCAN (C-73).

$99 million for reentry/diversion programs for justice-involved populations (C-73).

$20 million for pilot programs to transport voluntary/involuntary commitment patients without using law enforcement (C-73). While the bill does not specify where the funds from this pilot program will go, I find it likely that they are expanding the number of contracts with G4S, a private security contractor that some county commissioners have hired to take over the role of transport, such as Forsyth County.

$5 million to test out the “collaborative care model”, which shifts some basic mental health care away from specialists and onto primary care providers (C-73).

~$30 million in grants addressing substance use to nonprofits and counties. Notably, these focus on behavioral treatments. The budget cuts all state funding for the NC Harm Reduction Coalition.

~$40 million in funding to nonprofits and counties for providing behavioral health or developmental disability services.

$24 million for cigarette/e-cig prevention in 4-12th graders, funded by NC’s settlement with JUUL labs (C 125).

$10.7 million over two years in competitive grants to UNC institutions for research on opioid abatement (B-48).

While state officials have lauded such appropriations as “once in a lifetime” investments, there is some concern that the operative word is “once,” when it comes to state-run facilities. These discretionary items are largely funded through the non-recurring ARPA fund. Thus, it is unclear if future budgets will maintain the infrastructure—especially in the context of rising tax cuts.

For the private mental health system, however, there is reason for optimism. Funding will flow not only from the state purse but from Medicaid expansion beneficiaries empowered to spend mostly federal dollars. According to Secretary Kody Kinsley, Medicaid expansion will bring NC around $450 million per year in additional funding for behavioral health services. The impact of this change on the workforce and infrastructure problems that plague NC’s mental health system remains untested, but there is evidence that improvement may be coming. An analysis by the University of Michigan found that Medicaid expansion states licensed and retained more mental health professionals than non-expansion states. Another study showing an increase in the use of outpatient mental health services in expansion states suggests that there will be greater demand for new mental health practices around the state.

H.B. 259 also included a large change in state mental and behavioral health policy. The legislature handed over management of local management entities and managed care organizations (LME-MCOs) to Kody Kinsley, NC’s DHHS secretary. The LME-MCOs are healthcare networks contracted by Medicaid to provide behavioral healthcare to Medicaid beneficiaries across the state. The quality of LME-MCO services has not always been praised, resulting in constant frustration for the state legislature. Transferring control to Kinsley, who directly oversees the payment of the plans through his role as DHHS Secretary, is thought to make the LME-MCOs more accountable to the needs of North Carolinians. It is worth taking a moment to nod at the bipartisan trust Secretary Kinsley has built to allow this transition. Republican state Senator Jim Burgin was quoted by NC Health News saying, “We feel like the secretary is closest to the situation to make those tough decisions,” adding, “he knows we are here to help him and to get this right.” In the entire budget, this may be the only case where the legislative branch cedes power to the executive.

Rural Health

Since 2005, twelve rural hospitals in NC have closed or shuttered their inpatient services. This amount is more than California, which has nearly four times NC’s population. It is more than any other state except Texas and Tennessee, neither of which has expanded Medicaid either. The statistic underlines a critical workforce and infrastructure challenge that faces rural communities in North Carolina, which already suffer from worse economic and health outcomes than their urban counterparts.

H.B. 259 prioritizes investments in rural health, largely by transferring $420 million from the ARPA fund to a new project called “NC Care” directed by the Board of Governors of the UNC System and administered by ECU Health and UNC Health. This program, explicitly to improve rural healthcare infrastructure, includes the following provisions, all designated in two-year terms:

$210 million for three new rural health clinics and a $150 million investment in “community-owned” rural hospitals (H-9).

$10 million for the creation of a clinically integrated network between UNC Health and ECU Health to streamline patient care (C-70).

$50 million for a regional behavioral health facility in Greenville (H-8).

On top of these provisions, H.B. 259 adds several others aimed at addressing the rural health infrastructure and workforce crisis, including:

$25 million in loans to rural hospitals in a “financial crisis” (C-70).

$50 million in loan repayment programs for health providers in rural areas and $16 million in forgivable loans to primary care providers and psychiatrists working in qualifying counties (C-70 and C-71).

$20 million to expand telehealth in rural areas (C-71).

H.B. 259 also includes policy change that would allow rural hospitals to become designated “rural emergency hospitals” which would bring them increased federal funding while subjecting them to new regulations (p. 252).

It is worth looking out for the results of the above policy changes and appropriations. While investments in rural health are desperately needed, they are not guaranteed to succeed. A 2021 analysis by the NC Rural Health Research Program, created when the “rural emergency hospital” designation was first established, estimated that only one hospital in NC would make the transition. Telehealth use has sharply declined since the pandemic, representing under 0.4% of Medicaid claims in June 2023 in rural areas. It will be interesting to see if H.B. 259’s telehealth investment and NC’s massive broadband initiative will increase service use. Perhaps most importantly, there remains the question of whether a handful of medical centers and provider incentives were the best use of ARPA funds in rural areas. While Medicaid expansion will undoubtedly help these folks access medical care, it likely would have been more effective to invest ARPA funds in flagging rural public health, which addresses the health behaviors and economic, social, and environmental determinants that are estimated to constitute 80% of health outcomes.

Public Health

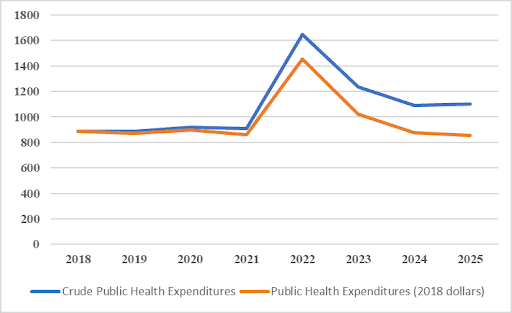

As we have seen, H.B. 259 generally makes an effort to meet the moment and ramp up funding for health services. In the field of public health, the results are less exciting. As shown in Figure 1, NC’s public health expenditures, controlling for items that have shifted around on the budget, are back to pre-pandemic levels in inflation-adjusted terms. Considering the growth in NC’s population and based on the author’s calculations, this represents a projected 10% drop in public health spending per person from 2018 to 2025.

Figure 1: Crude and Inflation Adjusted NC Public Health Expenditures ($Millions)

Source: Public health spending drawn from H.B. 259 committee report, S.B. 105 committee report, H.B. 966 committee report, S.B. 257 report. Inflation adjustment through BEA CPI Inflation Calculator.

These cuts do not come evenly. Figure 2 shows a sample of public health expenditures that is representative of public health spending. Certain areas in critical need such as public health surveillance and funding for the Medical Examiner’s office have risen. Other areas focused on disease prevention and healthy behaviors have received slow funding cuts throughout the pandemic in inflation-adjusted terms. Moreover, much of the state’s public health funding is financed by federal grants, such as nearly $300 million from the CDC in 2022. This funding exaggerates the state’s role in public health investments.

Figure 2: Inflation Adjusted (2018) Public Health Expenditures by Category ($Millions)

Source: Public health spending drawn from H.B. 259 committee report, S.B. 105 committee report, H.B. 966 committee report, S.B. 257 report. Inflation adjustment through BEA CPI Inflation Calculator.

There are only a few public health items for which H.B. 259 grants appropriations above the minimum from state resources. These include the following:

$22.5 million over the next two years on smoking and e-cig cessation programs for 4-12th graders funded by NC’s $40M settlement with Juul labs (C 125).

$8 million over two years to digitize state death and vital records.

Provides funding for the chief medical officer to establish new autopsy centers, receive increased fees for autopsies, and conduct toxicology screenings on all child deaths (C 120).

Grants an additional $50,000 per year to each local health department (C119).

There is nothing wrong with the appropriations above. Indeed, the focus on understanding child deaths and preventing smoking is laudable. Still, H.B. 259 leaves major issues that had compounded before COVID-19 unsolved. One 2021 analysis found that NC’s public health budget fell 27% in inflation and population-adjusted terms from 2010 to 2018. These cuts had a dramatic effect. Two reports using different methodologies – one including federal and state spending and the other only including state spending – each ranked NC among the bottom 5 states in public health spending per capita. By quickly reverting to pre-pandemic public health spending levels, H.B. 259 fails to address the issues that built up before the pandemic.

There are critical needs in the categories that H.B. 259 has let languish. NC’s health report card from the Commonwealth Fund reveals that areas where health outcomes are worsening include vaccinations, preventable disease onset, obesity, and opioid use. The NC Child Health Report Card gives the state a “D” or “F” for each of the four indicators related to health risk factors, such as healthy eating and active living. These needs could be better addressed by spending on prevention, health promotion, and early intervention—each of which has been stagnant for years.

Dried-up spending is also squeezing local health departments and decreasing the state’s capacity to respond to emerging health threats. In Columbus County, the health department’s state funding had fallen 39% from 2010 to 2021, leaving fewer resources to conduct programs from cancer screenings to community health assessments. Lack of funding limited local health departments' ability to respond to COVID-19 and will continue to hamper their ability to respond to emerging epidemic diseases. There is no need to recount America’s botched COVID-19 response, only to highlight the role of underfunded health departments in contributing to the crisis. It is surprising that less than half a year after the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency officially ended in May of 2023, by which point nearly 30,000 North Carolinians had died of the disease, the legislature is ready to continue underfunding public health “preparedness and response.” Predicting public health threats is hard, but anticipating our lack of preparedness is easy.

Special Issues

H.B. 259 includes several important provisions (or lack thereof) that do not fall neatly into the above themes. They include:

Additional UNC Health Investments: H.B. 259 invests in UNC Health beyond the new rural health clinics and the regional hospital. The bill puts forth the first $320 million in what is expected to be a $2 billion children’s hospital somewhere “in the Triangle Region.” According to the CEO of UNC Health, Dr. Wesley Burks, the new children’s hospital should take 8-10 years to build and be “comparable in clinical and academic scale to any of the top children’s hospitals in the country.” Although the budget does not specify where the remaining $1.7 billion for the project will come from, the first $320 million will come out of the ARPA fund, and UNC Health has indicated that $1 billion will be raised in private donations, with the rest coming out of their reserves (H-9). In addition to the children’s hospital, H.B. 259 appropriates $60 million per year for the University Cancer Research Fund to build on the work of the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center housed at UNC Chapel Hill (B-42). The bill also appropriates around $20 million over two years to rural UNC Health locations for improvements, a new residency program, and behavioral health upgrades.

Workforce Investment: H.B. 259 provides around $50 million per year in ARPA funding for an additional 120 school health personnel, such as nurses, counselors, and social workers (B 23). Over $30 million is appropriated for nursing education investment in community colleges (B-10). The bill also gives nursing faculty a raise of 10-15% (B-41).

Aging care services: H.B. 259 attempts to address the chronic shortage of skilled nursing and personal care workers by increasing Medicaid reimbursement rates (C-60). However, advocates are concerned that the increases will not be sufficient, leaving a continually understaffed system. In addition, the bill does not fund increases in any of the five legislative priorities from the NC Senior Tar Heel Legislature, a senior advocacy group. These priorities include increased funding to protect seniors from abuse in care facilities as well as for senior centers and services.

Analysis

H.B. 259’s health spending should be taken with a mixture of optimism and caution. Optimism, because the legislature has shown they can be convinced to make bipartisan decisions in the interest of the state, such as Medicaid expansion. Caution, because it took the state losing $5 billion federal dollars a year plus an extra signing bonus to reach that point. Optimism, as the bill makes historic investments in mental health and rural health infrastructure and workforce incentives. Caution, since these investments were made with one-time funding with no clear path to renewal in the context of aggressive tax cuts limiting future revenues. Optimism, as the bill funds areas of acute crisis including nursing pay, medical examinations, and people with a mental health crisis ending up in the ED. Caution, because the bill lets chronic issues such as underfunded public health services and care for seniors languish.

There is a reason this series began with tax cuts. The future of state services, including health, depends on them. Medicaid expansion will help fill some of the gaps, but mostly in areas where service providers are reimbursed for providing care. This does not include fundamental and unprofitable services that only the state provides, from ensuring the safety of our food and water systems to investigating complaints of nursing homes abusing seniors. As our corporate tax rate falls from 7% in 2013 to 0% in 2030, and the income tax rate falls from 6% to a potential 2.49% over the same period, it is uncertain where NC will produce the funds to maintain and improve discretionary spending priorities such as these. To be clear, H.B. 259 has life-saving health provisions. But we should be careful not to make a trend out of what may be an outlier.