Test for Unit 3: How Far Have We Come, and How Much Farther Must We Go, Towards Racial Equality?

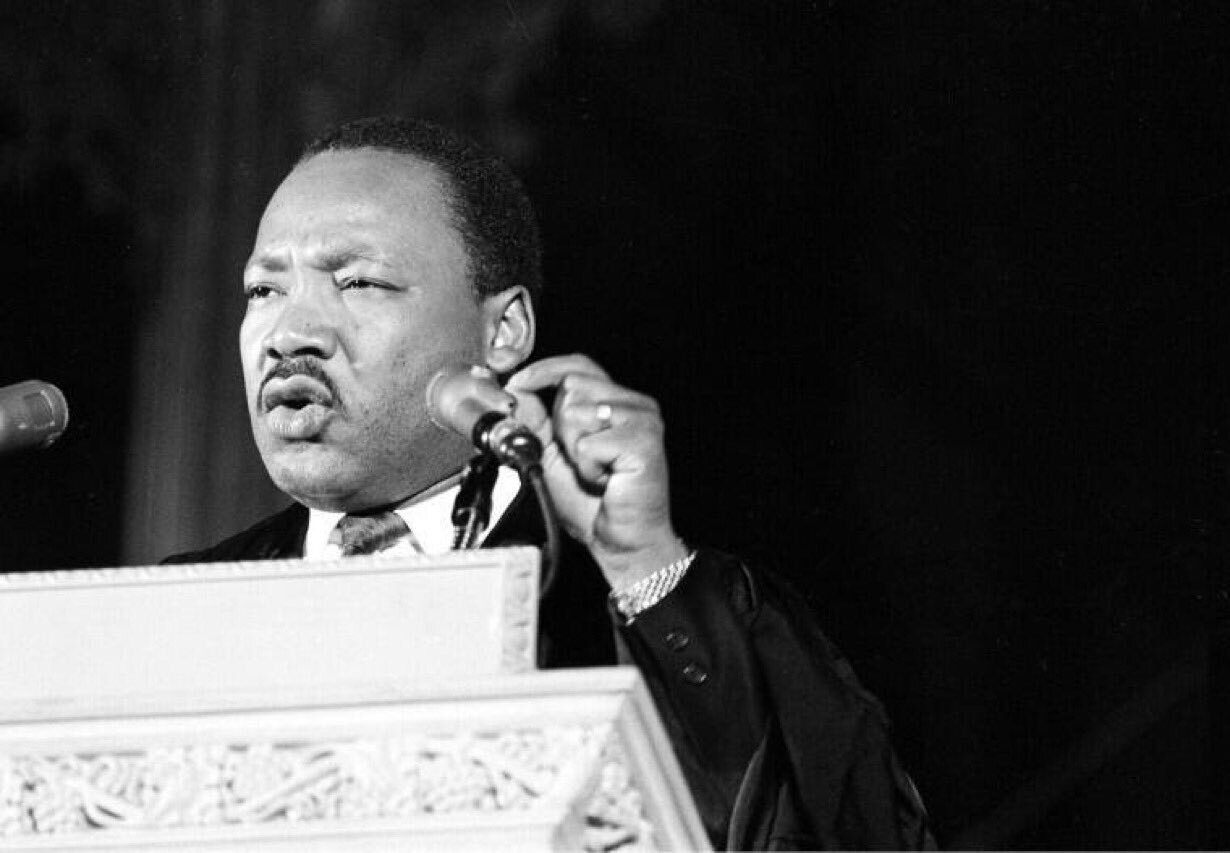

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., pictured giving a sermon at the Washington National Cathedral in Washington, DC on March 31, 1968 — five days before he was assassinated. Image: Michael Beschloss.

“Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! for ye are like unto whited sepulchres, which indeed appear beautiful outward, but are within full of dead men’s bones, and of all uncleanness. ”

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., while addressing the National Cathedral in 1968, prospected the yield that laid ahead for Americans to reap just five days before his assassination: “We shall overcome because the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends towards justice.” Yet the odyssey of Black progress in America has vacillated between a national ascension to expiation and its subsequent repulsion from opponents, with this tug-and-pull evolving from the blunt mistakes of racial bigotry that crack the door open just slightly enough for reason of racial justice to slip through. So, fifty-three years further along the arc Dr. King envisioned for America, has our nation yet come to the bend that leads to justice? Or are the gains of racial justice since 1968 largely nominal? Most important -- regardless of how far we’ve come -- is will we, Americans, harness today’s ambition for racial equality and take action to effectuate the aspirations of civil rights conceived since Reconstruction but which millions of Black American have yet to experience?

Since the Civil War, the hounds that flayed people of color have slithered away, taking more subtle forms behind the veil of underhanded oppression -- subverting the efforts toward equality away that are a bane to the new draconian state. We are now without chattel slavery and King Cotton Diplomacy; yet, under the guise of penal labor, many are still held by the bondage of cages, engaged in State-sanctioned labor for private economic profit and subject to an under-caste of second-class citizenship. Voting is now possible from when before it was a mortal danger: burning stakes and White mobs no longer bar us from the ballot nor do literacy tests, grandfather clauses and poll taxes. Instead, Gerrymandering (see: North Carolina State Legislature) and voter suppression (see: 2021 Georgia voting bill) tactics are at the vanguard.

There is no more need to fear the noose as we walk outside. Instead, police brutality has exchanged Emmett Till for Eric Garner; Selma Trigg and Lillie Belle Allen for Sandra Bland and Breonna Taylor (for a history of violence against Black women in America, see here); Thomas Finch for Laquan McDonald -- and all those whose names we do not know.

Some of our nation’s greatest triumphs lie in the political movement for historically underrepresented groups. Black and Brown politicians have held public office not just locally but in all three branches of the federal government, and the political agency of women soared, as highlighted by the record number of women and Native Americans elected to 117th Congress during the 2020 elections. Of greatest import, we were able to elect a Black President into office -- the success of Barack Obama has cemented him amongst our nation's most prominent presidents. Nonetheless, the degree to which the pulse of our nation really enjoyed the greatness of Black political triumph in Barack Obama was most clearly reflected in Donald Trump’s election and presidency.

This vacillating progression and regression, rife with paradox and lacking unabridged moral desert, has prompted Ta-Nehisi Coates to argue that the arc of the same universe to which Dr. King believed bent toward justice . . . . most clearly bends towards chaos. The extent to which we have lived up to the “goals” of Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, Reconstruction and its amendments, and those of Malcolm X, Ella Baker, Martin Luther King Jr., Fannie Lou Hamer, and the Civil Rights movement, has been the paradigm of two steps forward and one step back. The opportunities for equality evoked by the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments have infused our nation with unprecedented fairness -- but that is largely because the bar which we had to hurdle to achieve such “unseen heights” of co-racial achievement in American history was not difficult to clear. Furthermore, it’s become a fad for people to decry injustice, but when the bill is flipped on most folks’ table to take the responsibility of rectifying our wrongs most still can’t help but cling to America’s system of benefiting white -- a system borne from a history of dropping others to their knees to elevate themselves. Mr. Coates brands that history as America’s “bloody heirloom.” This is an heirloom still drenched with the blood of slaves and accented by the blood spilled from each lash inflicted today.

Report Card: America’s Racial Progress Since the 1960s

Overall, Black education rates have increased in high school and college. Nonetheless, stark disparities persist between Blacks and Whites in higher education, among other fields. Image: U.S. Census Bureau

One way to understand how Blacks as a race have both simultaneously advanced and stayed in subversion is to compare Black achievement from the 1960’s to that of Blacks today, and then to compare the gaps between Whites and Blacks in the 1960’s to the gaps between Whites and Blacks today. These gaps can be categorized in many tangible fields: Education, income, poverty, unemployment, health, and homeownership (Note: much of the data below comes from a 2018 report published by Janelle Jones, John Schmitt, and Valerie Wilson in the Economic Policy Institute).

For Blacks, both high school and college graduation rates have increased. Since 1968, the percentage of Blacks with a high school diploma has jumped from 54.4% to 92.3%. Consequently, the gap between White high school graduation rates and Black graduation rates has decreased from 20.5% to 3.3%. Yet, spanning the same time frame, Black college graduation rates have increased modestly: from 9.1% in 1968 to 22.8% in 2018. Accordingly, Black students are still half as likely to graduate college as White students.

Furthermore, increases in education have not translated to substantive economic success for the Black community. In the workforce, the hourly wage of black workers increased by 0.6% per year from 1968 to 2016, outpacing the 0.2% increase of White workers per year over the same time. This has equated to the average Black worker still only making 82.5 cents on every dollar made by the average White worker. When looking at household income, the discrepancies between the earnings of Whites and Blacks are even more stark. Although Black household income increased by 42.8% from 1968 to 2018, White household income spanning the same time increased by 36.7%, leaving the annual income received by Blacks to still be on average only 61.2% of White income. Additionally, when measuring economic data of Blacks against almost every other significant marker of improvement, the data fail to show any signs of consistent progression toward equity. Black unemployment has actually increased since 1968 up through just before the COVID-19 pandemic, jumping from 6.7% to 7.5%. Homeownership and equity, significant markers of wealth, have remained practically unchanged for Blacks (41.2%), while White homeownership (71.1%) in comparison has widened to nearly 30 percentage points higher than Blacks since 1968. And, although the familial net worth of wealth of Blacks has increased sixfold since 1963 from $2,467 to $17,409, the family net wealth of Blacks today is the same number as the median White family’s net wealth in 1963, while the median wealth of White families has increased to $171,000 over the same time frame.

Median rates of wealth by race shown above in blue; average rates of wealth by race shown above in orange. Graph: The Federal Reserve

Thus, it can come as no surprise that Blacks are 2.5 times more likely to be in poverty than Whites. The ramifications of such discrepancies intensely suffocate opportunities for Blacks in all arenas of our society -- effectively barring a whole race from a slice of the American dream. Among these ramifications is the jeopardization of Black health with respect to the treatments afforded for White health. Despite advancements in modern medicine, the likelihood of infant mortality for blacks compared to Whites is higher today than it was in 1968 (1.9 times greater in 1968, 2.1 times greater today). The COVID-19 virus has exacerbated racial health disparities. Before COVID, Blacks were already predicted to live about 3.5 fewer years than Whites -- a significant gap. A year after COVID and after vaccines have begun to roll out, non-Whites are still dying at disproportionate rates; Blacks died at a rate 1.2 times that of Whites between December 2020 and March 2021 alone. These are problems of disposition, not faculty.

Today’s Freedom Isn’t All Free

Inmates at Angola State Penitentiary, located in Louisiana, do labor similar to and under similar conditions of enslaved people in the Antebellum south. At the onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic in 2020, inmates described horrific conditions causing the virus to spread throughout the inmate population as the prison imported the state’s sick individuals. One prisoner described it as a “war.” Image: Hard Crackers

Regardless of some of the discrepancies between Blacks and Whites, the splintering of the divisive bridge between Black and White freedom (in its most literal definition) is our most highly touted achievement. The Civil War is heroically credited for this defining triumph of racial equality in our nation, with America having finally been procured that the inconvenience of Black liberation is a damage of collateral, not catastrophe. The war effectively ended slavery and paved the way for the Reconstruction amendments that followed. I pointed out earlier that we have exchanged the cotton wrenching slavery of then for the concrete plantations of mass incarceration of now (Black and Hipsanic people alone constitute 56% of the incarcerated, yet only 34% of the total U.S. population). I will not dive deep into this subject -- I only wish to point out a few things (a voluminous book could be written just on this aspect of racial inequality, and many have so written). Some of these are points that have stuck with me since a presentation I gave in 2019 on Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow. I feel it would be inadequate if I did not mention them, although that feeling is most likely tied in with the bias I have to my own personal research as opposed to what is warranted by the flow of this essay.

First, mass incarceration is fueled by preying on drug addiction. The conception that most crime is violent, and that most of the people in jail have committed violent actions prior to their incarceration, is farcical. Since the 1970s, violent crimes have accounted for less than a 1% increase in total crime, and less than 8% of all crimes are violent (Alexander, The New Jim Crow, Chapter 4). In Chicago, which perennially has one of the highest murder rates in the U.S, 72% of criminal cases constituted drug charges in 2009, with 70% of them being a class 4 felony of possession: the lowest felony charge (Alexander, The New Jim Crow, Chapter 5). This segues into the next point: the police target drug users, not drug sellers. This creates a cycle of entrapment, because addicts are more prone to committing crimes of desperation to fuel their addiction (See: Lockyer v. Andrade).

Point three: mass incarceration is economically beneficial. Look no further than forfeiture laws and grants. Michelle Alexander cites that from 1988-1992, drug task forces funded by Federal Byrne Grants, seized over $1 billion in assets, of which they kept 80%. Aside from legislative reaping of wealth by locking up Black and Brown bodies, inmates are subjugated to practically a similar manner of labor as enslaved people were. At Angola State Penitentiary -- a complex larger than Manhattan and spanning several former slave plantations -- prisoners are forced to pick cotton in addition to other hard labor while horseback riding guards manage them. They are even punished by being sent to the “hole” for not doing the labor. Finally, arguably the greatest blatant constitutional affront by the tactics of mass incarceration is the counting of prisoners toward the electoral college. Much like the three-fifths clause, prisoners count towards the voting population yet are not permitted to vote, and most federal prisons are located in predominantly rural-white counties. Thus, the population of prisoners adds a disproportionate advantage for white counties towards voting by giving them greater weight in the electoral system. And this added weight is even more disproportionate than the counting of slaves as three-fifths a person, because today Black people are counted as a full person and so, too, do prisoners count as one person.

Unit 3

In 2020, we witnessed enough raised awareness, promises made, and protests. Now we need to see results. Image: Latino USA via AP / Ashley Landis.

As we emerge from the transitory period that was 2020, we have an opportunity for a third era of civil rights expansion. Never has America been so ostensibly receptive to moving forward in racial progress. But, like the other periods of hope in our country, the ability to concretely effectuate change for civil rights is quickly fleeting. Biden’s narrow win over the former President, and still white supremacist figure, Donald Trump, and then the January 6th insurrection that followed, prove that for all the noise of commitment to racial justice White America promised in the summer of 2020, we are barely limping along in a race that only just started.

We do not need more racial awareness, and we did not need it before George Floyd died on May 25, 2020. The angst that the many in the white community said they finally felt, after witnessing Mr. Floyd gasp for his mother as he died, is what the rest of the non-white world has been feeling for all of their life. We do not need Whites to start reading James Baldwin and Toni Morrison, Ta-Nehisi Coates and Michelle Alexander, just to “educate” themselves. We need to tear down racial indifference, and that happens by trying and stumbling and getting up and walking. Put down the books, close the tab that you have open for this article, and start doing. Each of us will inevitably fail at first. No one has the answer for what “doing” means for you specifically (so, don’t ask, “What should I do”). It might be calling your Congressperson to voice support for the HR-1 voting rights legislation, lobbying your local representative and state educational board to stop drawing public school funding from district property taxes (a practice which creates disparities in the quality of education between white and Black communities), or outright refusing to vote for candidates who don’t have a track record of racial justice activism -- regardless of if they’re in your party. It does not matter if the first step is in the completely wrong direction -- keep walking, ready to listen at every step, and the force of the world will push you to where it is you need to go and what it is you need to do.

Lastly, when each of us starts walking and figuring out what direction it is we need to go, we must remember: we are not close to the point of racial equality, and that is not the problem. Racial equality, and the goals we aspire to fulfill from Reconstruction and the Civil Rights movement, were not expected to come in absoluteness so soon. The problem lies in believing that we are close; in believing that the institutions around us are entirely different than those of the past just because their appearances and the ideals they espouse are different. When we buy into what is right in front of us, without attempting to read between the lines, we cultivate indifference in ourselves -- with our conscious decision to suck on the palpitation of satisfaction forever suffocating our ideals of equality. And this ethic does not stem from just the conservative community but equally from liberals as well. As each of us walks forward to find how we can come together, we must attempt to emulate the constant inquisition of James Baldwin -- who writes in Notes of a Native Son, “I love America more than any other country in this world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”