The Real Red Zone: Punts Over Prevention

Participants in a "living display" at an event at Ellsworth Air Force Base during Sexual Assault Awareness and Prevention Month in 2016 (source)

Sports are an instrumental part of American culture, and one of the most valued components of the American college experience. From basketball and football to soccer and swimming, it’s hard to imagine American universities without also picturing tailgates, game days, and for Carolina students, rushing Franklin Street after a monumental win. Unfortunately for victims of sexual assault, athletics on college campuses often do not bring those same things to mind.

An initial Google search of the phrase “Red Zone” yields results that are almost exclusively from the National Football League. The NFL offers this special game-day exclusive broadcasting on Sundays during the NFL regular season, but the corporate mammoth is most likely unaware that “Red Zone” holds a different connotation to young collegiate women.

Outside of football, the Red Zone is a term used to define the period from August to November in which the number of sexual assaults on college campuses is highest, a fact confirmed by the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN). According to studies, the first six weeks of this four-month period are the most dangerous, and female-identifying first-years are the most vulnerable to an attack.

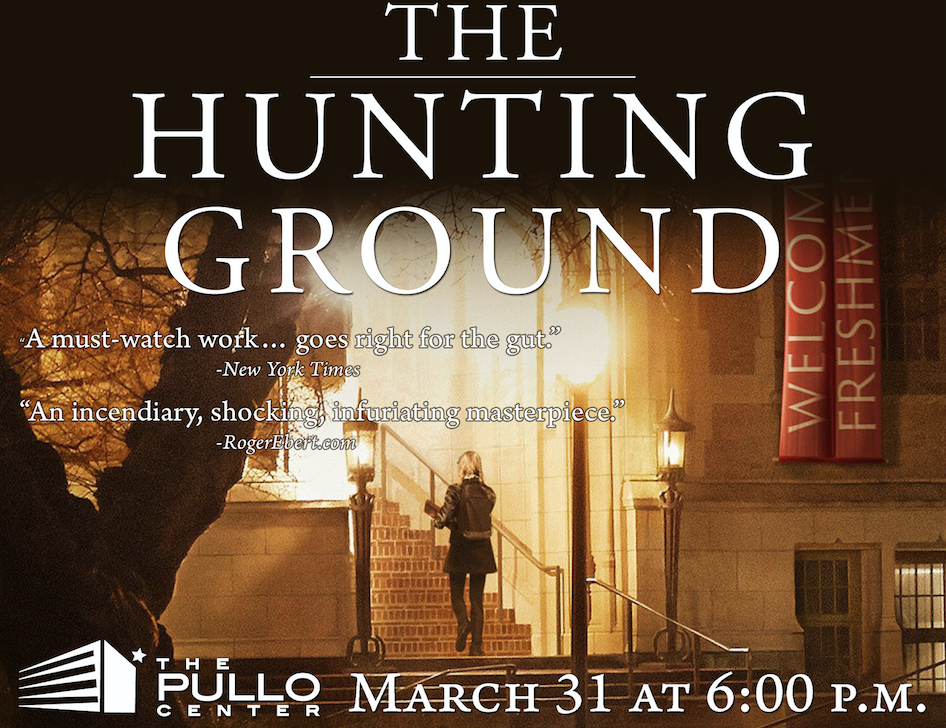

A flyer for a screening of the documentary "The Hunting Ground" at Penn State York (source)

The lack of awareness about the Red Zone is concerning, especially considering that UNC is one of many universities that has faced criticism for its handling of sexual assault cases, largely discussed in the documentary “The Hunting Ground” and similarly in the media. People like to pin the sexual assault epidemic on the “risky business” culture of American college campuses but fail to acknowledge this argument is a form of victim blaming. College students should be able to have a good time without the looming fear that it is statistically possible that their basic rights may be violated.

Initial Google search results of the NFL’s Red Zone are ironic given that student athletes are statistically the most likely to be confused about consent and to identify with hypermasculinity than any other demographic on college campuses. Hookup culture is often status-based, and college athletes are typically of a higher status with their standing in a multimillion dollar industry. Status single-handedly undermines any possible intervention from a bystander; it’s one thing to save an intoxicated person from a dangerous situation, but when that intoxicated person is in the arms of one of the most popular students on campus, it can be difficult for people to intervene. Moreover, the amount of protection that athletes receive from administrators easily overpowers those who try to speak out about their assault.

There is a fundamental issue with how we prepare our children for college on the basis of nothing but gender identity, and it goes beyond the campus itself. It stems from a long history of systemic gender roles and oppression. Many sexual assault initiatives in the past have placed the responsibility on the potential victims to avoid being violated, as though restricting their actions to a few behaviors would make their aggressors back off. Instead of men being taught how to refrain from committing an assault, women are taught what to do to avoid such an incident. Some universities have adopted mandatory trainings that teach students how to intervene if they see a potentially dangerous situation, but this form of prevention is too little too late given that students with problematic views about consent are unlikely to change after one online training. The problem lies in phrases children hear growing up such as “He was being mean to you? That must mean he likes you,” and “Act like a lady.” When someone says “Act like a lady,” what women really hear is “Be complacent in your oppression.” As a UNC student, at the very least you can do is undergo One Act and HAVEN training. You should make your peers aware of campus resources and encourage everyone to watch the documentary “The Hunting Ground,” but most importantly, you should actively call out those who encourage toxic behaviors. It’s on Google and university administrators alike to show more regard to campus sexual assault than to football exclusives, but it’s on us to hold our friends, acquaintances, and campus celebrities accountable for their actions.